Projects Fund Very Close To Their Goal Amount

One thing that I’ve noticed happening over and over is that crowdfunding projects fund really, really close to their goal amount. Not much higher.

The two biggest reasons that I can think of for so many projects funding so close to their goal are:

- Bands ARE setting their goal amount very close to their true fundraising ability, or

- Individual consumer incentives discourage participation once the goal amount is reached, effectively capping the project near a funding ratio of one.

Neither of these implications are ideal when it comes to a crowdfunding project.

If bands are indeed setting their goal amount close to their fundraising ability, then they are introducing unnecessary risk to their project of failure!

If individual consumers are not properly incentivized, then neither is the group of potential backers so projects lose their upside funding potential.

Let’s take a look at the numbers that tipped me off to this phenomenon and then let’s discuss a few things you can do to decrease your project’s risk of failure and simultaneously increase its upside potential.

The Funding To Goal Ratio

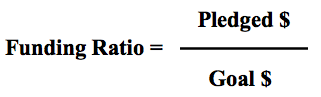

The best way to look at a whole bunch of projects and how their amount fundraised compares to their goal amount is by calculating the ratio of the two.

So, when I refer to a crowdfunding project’s funding ratio, I mean the total dollars pledged divided by the goal amount.

Kickstarter and Indiegogo only show you the amounts, so you must calculate the ratio, while RocketHub and PledgeMusic both show the ratio by default.

A ratio (or percent) is useful because it will have the same meaning for any size project.

A $1000 goal with $1050 funding would have a an absolute difference of only $50 and a ratio of 1.05. A $10000 goal with $10500 funding would have an absolute difference of $500 but still have a ratio of 1.05.

If we looked at the absolute difference in funding, these 2 projects would look very different. But when we account for size of the project and compute the ratio, we see that they are fairly similar.

Projects with a ratio greater to or equal to 1 have funded, while anything below 1 is a failure. The higher the ratio, the more the project blew their goal out of the water. The lower the ratio, the worse they did.

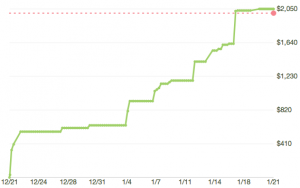

Notice how this project barely makes it to the goal amount. (Graph courtesy of now-defunct Canhekick.it)

I have been tracking this statistic for projects over the entire course of our 100 Music Kickstarters and I noticed that so many projects are limping in at or just over their goal amount.

So, I want to look at all the projects as a whole so I can confirm whether this is happening or not and, if so, to think about why it’s happening.

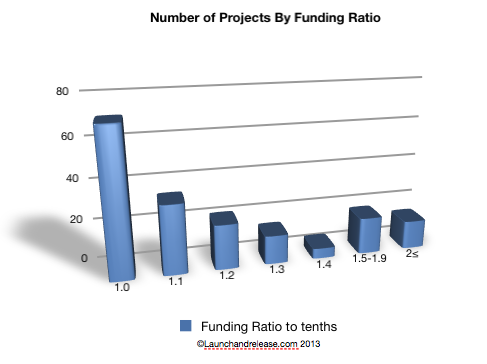

FYI – I have tracked this small sample of projects by hand and selected only successful projects, 178 observations in all.

Now, I want to see a simple, visual summary of how projects are doing compared to their goal amount.

This distribution of funding ratios shows about what you would expect to see when projects are setting their goal amount approximately equal to their perceived fundraising ability: lots of projects at or near 1.0 (whose funding level is very close to their goal amount) with a more or less decreasing amount of projects as you move to higher funding ratios.

Why would we expect this? Let’s put it another way.

If you were able to design the perfect experiment where you asked a whole crap load of bands to guess how much they could fundraise and then sent them out to do it, these are most likely the results you’d tend to see:

- A few bands would WILDLY overestimate their ability and their ratios would be really low, like under 0.25 (they could only raise a quarter of what they thought they could)

- Some bands would overestimate their ability and have ratios that are on the low side, say between 0.25 and 0.8

- Many bands would get it about right, between 0.8 and 1.2

- Some bands would underestimate their ability with ratios between 1.2 and 2.0

- A few bands would WILDLY underestimate their ability, blow their goal out of the water and come in at 2 or above.

If you are scoring at home, I just described a normal distribution skewed right (due to truncation at 0 on the left side but infinite on the right side of the X-axis) which would look like this:

Right skewed, normal distribution

Okay, I will stop geeking here. You have no idea how much fun I just had explaining that. I can never get anybody to listen to me about this stuff. I really could go on. But I digress…

Notice that my fancy 3D graph of funding ratio looks about like the right side of the right-skewed, normal distribution (to the right of the Mode).

So, yes, the distribution of funding ratios looks about like you would expect to see when bands are, on average, attempting to estimate their fundraising ability and then setting their goal about there.

Now, what can you do about this?

Decreasing Risk of Failure

When it comes to crowdfunding, you may have a legitimate reason to choose a goal amount very close to what you think you can achieve.

The most obvious reason here would be that the amount you can raise is the same as the minimum scope of project you are willing to do. You just wouldn’t do anything less!

But if you are willing to do a simpler, cheaper project than what you ideally envision, then setting a lower official goal amount will alleviate risk of failure. Adding a flex goal will help preserve your ability to reach your true, envisioned goal amount.

You want to record a studio, 6 song EP that will cost you $3000 with your local one-stop-shop studio/engineer/producer guy.

You have talked to a lot of your friends about this and you have been constantly asked by fans about when you will release an EP. Everybody has been soooo supportive! You are pretty sure that you can crowdfund $3000.

What do you do?

If you set your goal amount at $3000 and it turns out that you are wrong, you are in serious jeopardy of failing.

But, if you decide that your Minimum Viable Project is a live EP that will only cost $1500, you can just set your goal there and almost undoubtedly hit it.

You really do remove the risk of failing by taking this approach!

Increasing Project Upside

This is an area where it isn’t completely clear to me what the implications are.

I started out this project assuming that bands would want to maximize their fundraising regardless of their envisioned project budget. There is always more you can do with recording budget (or the ever-ambiguous marketing budget).

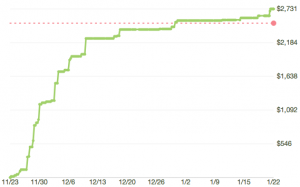

Notice how this project gets close to the goal by half way but then completely loses steam. (Graph courtesy of now-defunct Canhekick.it)

But at this point, in seeing projects and talking with artists, I don’t think this assumption holds.

For sure, some artists view their fans as a singular entity that the artist doesn’t want to take advantage of because they think of crowdfunding as ‘asking for money’.

Or possibly artists are not sure what they would do with extra money so they don’t want the burden of bringing their product up to a level that they aren’t sure how to achieve.

All of this being said, if you are an artist that does want to maximize your crowdfunding, it is super important that you properly incentivize individuals to continue pledging after you’ve reached your goal.

I am not talking about the incentive to purchase a reward or not.

I am talking about the incentive to contribute to the project.

This is achieved either by just being an awesomely, likable person whose inner circles just feel the need to contribute or, more likely, by demonstrating how awesomely bad-ass you can make your project with extra budget.

Art for Amanda Palmer’s Kickstarter-funded album

When fans took Amanda Palmer’s project to the moon and back, it wasn’t because they all just wanted a CD and book, it was because they believed that Amanda would use their gift in a professionally superb manner that would contribute to the quality of the product. They weren’t contributing to her just because they liked her, they were contributing to her craft because they believed in her!

You decide to set your goal amount at $1500, the amount your Minimum Viable Project will cost (live recording).

But you have tons of great ideas for instrumental layering and vocal production and you REALLY, REALLY WANT to record in a studio.

This is what you need to communicate very, very clearly to fans.

“Our official goal is $1500 which will pay for a 6 song live recording. But we know that we can crush the holy living $h!t out of a studio recording. We have spent tons and tons of time producing intricate instrumental and vocal arrangements for these songs. This is the product that we want to bring to you so we are setting an unofficial goal amount of $3000. When we hit that, you are going to be delivered one heck of an EP.”

Now your fans have the incentive to push your funding towards your real goal.

Bringing it all together for you, think of your 50, 100 or 150 backers as one person who will look at your project’s purpose, then glance at your goal amount, then glance over to your amount raised and then decide what to do.

At that point they either think “oh ok, the band really needs to buy a Keytar, their goal is $2500, they’re at $2593, looks like they got’r handled. No need for me to pledge!”

Or, they think “Well, they hit their goal but I see that with another $1500 they could hire Richie Sambora to rock the hell out of the solo in their single. Sign me up!”

The Takeaway

Over forty five percent (45%) of music crowdfunding projects fail according to Kickstarter.

One of the biggest causes is too high of a goal.

Don’t open up your project to unnecessary risk by setting a goal amount that is too close to your true ability to fundraise. Instead, decrease your official goal (not your actual goal!) to the level of your Minimum Viable Project and then incorporate a flex goal strategy to preserve the potential for funding your envisioned project.

Additionally, most projects hit their goal and then stall out. This happens when there is no collective upside for your fans.

If you want to maintain upside potential for your project, you must incentivize individual consumers to pledge additionally by adequately demonstrating your ability to raise your project’s quality with the additional funding.

Crowdfunding is grown older with time and now people understands more about there needs in terms of funds and how they can generate them. So as a result a lot more goals are achieved than it was earlier.